Contents

Contents

Quick facts

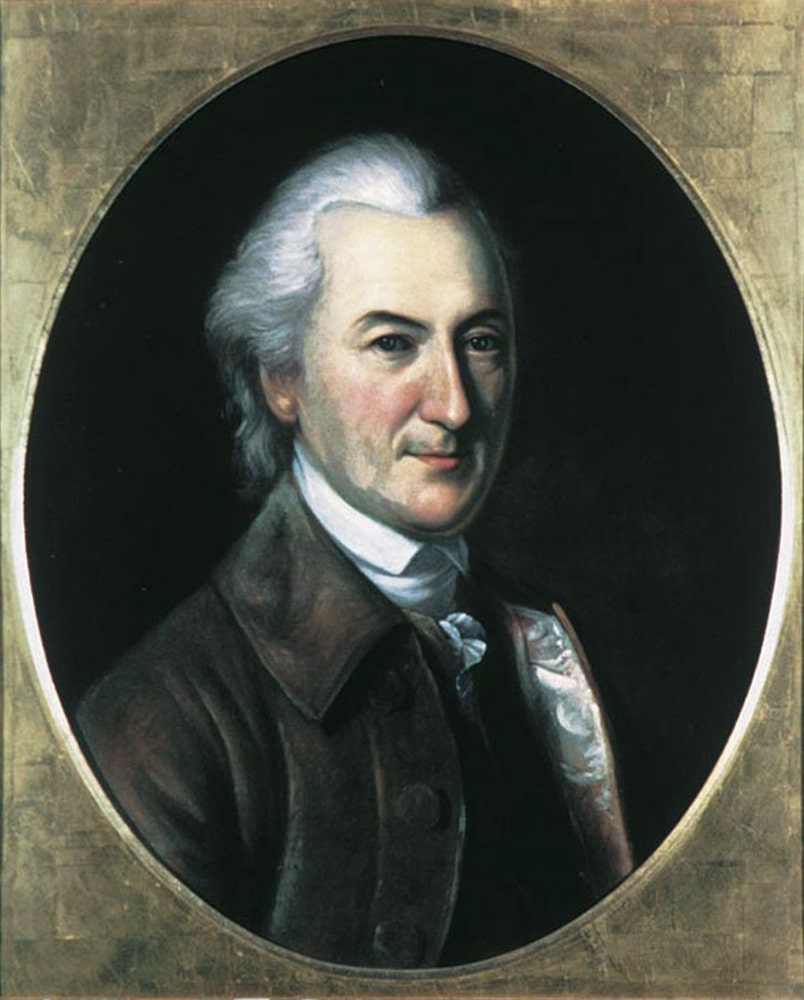

- Born: 8 November 1732 at the family plantation in Talbot County, Maryland.

- John Dickinson was known as the “Penman of the Revolution” for his influential letters and writings that argued for American rights and governance.

- He authored the “Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania,” a series of essays that articulated the colonial opposition to the Townshend Acts imposed by Britain.

- Dickinson served in the First and Second Continental Congresses and played a key role in drafting the Articles of Confederation.

- Although he abstained from signing the Declaration of Independence, believing in reconciliation with Britain, he later enlisted in the Continental Army.

- He was a principal drafter of the 1776 Delaware Constitution and also contributed significantly to the 1787 draft of the U.S. Constitution.

- As President (Governor) of Delaware and Pennsylvania, Dickinson implemented policies to strengthen the states post-independence.

- His later years were devoted to legal and philosophical writings, including efforts to abolish slavery and promote religious freedom.

- Died: 14 February 1808 in Wilmington, Delaware.

- Buried in the Friends Burial Ground in Wilmington, Delaware.

Biography

American statesman and pamphleteer, John Dickinson was born in Talbot County, Maryland, in 1732. He moved with his father to Kent County, Delaware, in 1740, studied under private tutors, read law, and in 1753 entered the Middle Temple, London. Returning to America in 1757, he began the practice of law in Philadelphia.

Being under the same proprietor and the same governor, Pennsylvania and Delaware were so closely connected before the Revolution that there was an interchange of public men. He was speaker of the Delaware assembly in 1760, and was a member of the Pennsylvania assembly 1762 – 65 and again in 1770 – 76. He represented Pennsylvania in the Stamp Act Congress (1765) and in the First and Second Continental Congresses in 1774 and 1775 – 76, when he was defeated owing to his opposition to the Declaration of Independence.

He then retired to Delaware, served for a time as private and later as brigadier general in the state militia, and was again a member of the Continental Congress (from Delaware) in 1779 – 80. He was president of the executive council, or chief executive officer, of Delaware in 1781 – 82, and of Pennsylvania in 1782 – 85, and was a delegate from Delaware to the Annapolis Convention of 1786 and the Federal Constitutional Convention of 1787.

Dickinson has aptly been called the Penman of the Revolution.

No other writer of the day presented arguments so numerous, so timely and so popular. He drafted the Declaration of Rights of the Stamp Act Congress, the Petition to the King and the Address to the Inhabitants of Quebec of the Congress of 1774, the second Petition to the King, and along with Jefferson, The Declaration of the United Colonies of North America setting forth the Causes and the Necessity of their Taking up Arms (1775), and the Articles of Confederation of the Second Congress.

Most influential of all, however, were The Letters of a Farmer in Pennsylvania, written in 1767 – 68, in condemnation of the Townshend Acts of 1767, in which he rejected speculative natural rights theories and appealed to the common sense of the people through simple legal arguments. By opposing the Declaration of Independence, he lost his popularity and was never able entirely to regain it. As the representative of a small state, he championed the principle of state equality in the constitutional convention, but was one of the first to advocate the compromise, which was finally adopted, providing for equal representation in the Senate and proportional representation in the House of Representatives.

He was probably influenced by Delaware prejudice against Pennsylvania when he drafted the clause which forbids the creation of a new state by the junction of two or more states or parts of states without the consent of the states concerned as well as of Congress. After the adjournment of the Convention he defended its work in a series of letters signed Fabius,

which will bear comparison with the best of the Federalist productions. It was largely through his influence that Delaware and Pennsylvania were the first two states to ratify the Constitution.

Dickinson’s interests were not exclusively political. He helped to found Dickinson College (named in his honor) at Carlisle, Pennsylvania, in 1783, was the first president of its board of trustees, and was for many years its chief benefactor. He died in 1808.