Contents

Contents

Quick facts

- Born: 22 February 1732 at the family Pope Creek Estate (near present-day Colonial Beach, Virgina).

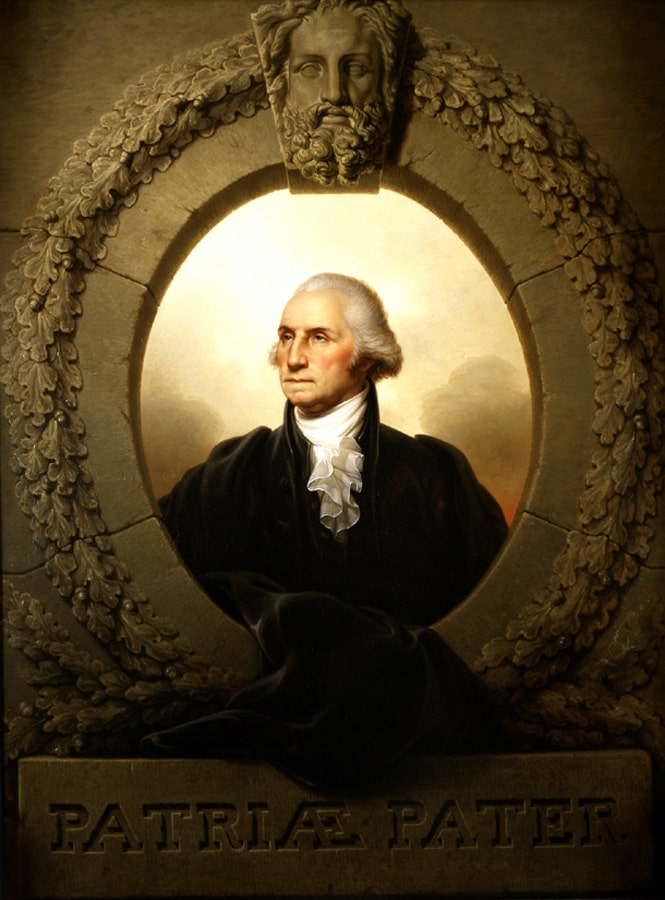

- George Washington served as the first President of the United States from 1789 to 1797 and is widely regarded as the “Father of His Country.”

- He was the Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, leading the American forces to victory over the British.

- Washington presided over the Constitutional Convention in 1787, playing a crucial role in the formation and ratification of the U.S. Constitution.

- During the American Revolutionary War, George Washington’s leadership at the winter encampment at Valley Forge (1777-1778) was crucial in maintaining the morale and cohesion of the Continental Army, despite severe hardships and lack of supplies.

- Washington engineered the pivotal victory at the Battle of Yorktown in 1781, collaborating with French forces under General Rochambeau and Admiral de Grasse, which led to the British surrender and effectively ended the Revolutionary War.

- Despite owning enslaved people, Washington’s views on slavery evolved over his lifetime, and he eventually freed his slaves, the only Founding Father to do so.

- Died: 14 December 1799 at Mount Vernon.

- Buried with his wife, Martha, at Mount Vernon.

Introduction

George Washington, Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army during the American Revolution and the first president of the United States, was born at Bridges Creek, Westmoreland County, Virginia, on 22 February 1732. His father, Augustine (1694—1743), married twice. First to Jane Butler, with whom he had four children, then to Mary Ball — descendant of a family which migrated to Virginia in 1657 — with whom he had six children, George being the eldest.

Early years

Of Washington’s early life little is known, probably because there was little unusual to tell. There is nothing to show that the boy’s life was markedly different from that common to Virginia families in easy circumstances — plantation affairs, hunting, fishing, and a little reading making up its substance. From 1735 to 1739 he lived at what is now called Mount Vernon, and afterwards at the estate on the Rappahannock River, near Fredericksburg, where his father usually lived.

His education was only elementary and very defective, except in mathematics, in which he was largely self-taught. And although at his death he left a considerable library, Washington was never an assiduous reader. Throughout his life he had a good deal of official contact with the French, but he never mastered their language. Some careful reading of good books there must have been, however, for in spite of pervading illiteracy in matters of grammar and spelling, he acquired a dignified and effective English style. Washington left school in the autumn of 1747, and from this time we begin to know something of his life.

He was then at Mount Vernon with his half-brother Lawrence, who was also his guardian. Lawrence was a son-in-law of William Fairfax, proprietor of the neighboring plantation of Belvoir, and agent for the extensive Fairfax lands in the colony. Lawrence had served with Fairfax at Cartagena, and had made the acquaintance of Admiral Edward Vernon, from whom Mount Vernon was named. In 1748, through the influence of Thomas, Lord Fairfax — the head of the family, who had come to America to live — Washington was appointed surveyor of the Fairfax property. He was only sixteen years of age, but an appointment as public surveyor soon followed.

The next three years were spent in this service, most of the time on the frontier. He always retained a disposition to speculate in western lands, the ultimate value of which he early appreciated. He seems too, to have already impressed others with his force of mind and character. In 1751 he accompanied Lawrence, stricken with consumption, to the West Indies. There he had an attack of smallpox which left him scarred for life. Lawrence died the following year, making George executor and residuary heir of Mount Vernon; the latter estate became his in 1761.

The French and Indian War

In October 1753, on the eve of the French and Indian War, Washington was chosen by Governor Robert Dinwiddie as the agent to warn the French away from their new posts on the Ohio River in western Pennsylvania. He accomplished the winter journey safely, though with considerable danger and hardship; and shortly after his return was appointed lieutenant colonel of a Virginia regiment, under Colonel Joshua Fry.

In April 1754 he set out with two companies for the Ohio River. On 28 May he defeated a force of French and Indians at Great Meadows (in present Fayette County, Pennsylvania), and his surrender at Fort Necessity shortly afterwards — despite a vigorous defense — was the first opening salvo of the French and Indian War.

When General Edward Braddock arrived in Virginia in February 1755, Washington wrote him a diplomatically worded letter, and was presently made a member of the staff with the rank of colonel. His personal relations with Braddock were friendly throughout, and in the calamitous defeat, he showed for the first time that fiery energy which always lay hidden beneath his calm and unruffled exterior. He ranged the whole field on horseback, making himself the most conspicuous target for Indian bullets, and, despite what he called the dastardly behavior

of the regular troops, saved the expedition from annihilation and brought the remnant of his Virginians out of action in fair order. Washington was one of the few unwounded officers.

In August, after his return, he was commissioned commander of the Virginia forces. He was 23.

For about two years his task was defending a frontier of more than 350 men with 700 men,

a task rendered the more difficult by the insubordination and irregular service of his soldiers, as well as irritating controversies over official precedence. To settle the latter question, he made a journey to Boston in 1756 to confer with Governor William Shirley. In the winter of 1757 his health broke down, but in the next year he had the pleasure of commanding the advance guard of the expedition under General John Forbes, which occupied Fort Duquesne and renamed it Fort Pitt (now Pittsburgh).

Marriage and the Mount Vernon Plantation

At the end of the year with the war in Virginia at an end, he resigned his commission. In January 1759 he married Martha Custis (née Dandridge; 1732—1802), widow of Daniel Parke Custis. The marriage brought him an increase of about $100,000 in his property, making him one of the richest men in the colonies; and he was able to develop his plantation and enlarge it.

For the next fifteen years Washington’s life at Mount Vernon, where he made his home after his marriage, was that of a typical Virginia planter of the more prosperous sort, a consistent member and vestryman of the Established (Episcopal) Church, a large slaveholder, a strict but generally considerate master, and a widely trusted man of affairs. His extraordinary escape in Braddock’s Defeat had led a colonial preacher to declare in a sermon his belief that the young man had been preserved to be the savior of his country.

But if there was any such impression it soon died away, and Washington gave his associates no reason to consider him a man of uncommon endowments.

His attitude towards slavery has been much discussed, but it does not seem to have been different from that of many other planters of that day. He did not think highly of the system, but had no invincible repugnance to it, and saw no way of getting rid of it. In his treatment of slaves, he was exacting, but not harsh, and was averse to selling them, except by necessity. His diaries show a minutely methodical conduct of business, generous indulgence in hunting, comparatively little reading, and a wide acquaintance with the leading men of the colonies — but no marked indications of what is usually considered to be greatness.

As in the case of Lincoln, he was educated into greatness by the increasing weight of his responsibilities and the manner in which he met them. Like others of the dominant planter class in Virginia, he was repeatedly elected to the House of Burgesses, but the business which came before the colonial Assembly was for some years of only local importance, and he is not known to have made any set speeches in the House, or to have said anything beyond a statement of his opinion and the reasons for it.

Conflict with England

Washington was present on 29 May 1765 when Patrick Henry introduced his famous resolutions against the Stamp Act. That he thought a great deal on public questions, and took full advantage of his legislative experience as a means of political education, is shown by his letter (5 April 1769) to his neighbor, George Mason, communicating the Philadelphia non-importation resolutions, which had just reached him. In this he briefly considers the best means of peaceable resistance to the policy of the ministry, but even at that early date faces, frankly and fully, the probable final necessity of resisting by force, and endorses it — though only as a last resort.

The following May, when the House of Burgesses was dissolved, he was among the members who met at the Raleigh Tavern and adopted a non-importation agreement — which he himself kept when others did not. Though on friendly terms with Governor Norborne Berkeley, Baron Botetourt and his successor, John Murray, Earl of Dunmore, he nevertheless took a prominent part in the struggles of the Assembly against Dunmore, and his position was always a radical one.

As the breach widened, he even opposed petitions to King George and Parliament. This, on the ground that the claims to taxation and control had been put forward by the ministry on the basis of right, not of expediency, that the ministry could not abandon the claim of right and the colonies could not admit it, and that petitions must be, as they already had been, rejected. Shall we,

he writes in a letter, after this whine and cry for relief?

The First Continental Congress

On the 5 August 1774, the Virginia Convention appointed Washington as one of seven delegates to the Continental Congress, which met at Philadelphia on 5 September, and with this appointment his national career began (with but two brief intervals until his death). His letters during his service in Congress show that he fully grasped the questions at issue, that he was under no delusions as to the outcome of the struggle over taxation, and that he expected war. More blood will be spilled on this occasion,

he wrote, if the ministry are determined to push matters to extremity, than history has ever yet furnished instances of in the annals of North America.

His associates in Congress at once recognized his military ability, and although he was not a member of any of the committees of Congress, he seems to have aided materially in securing the endorsement by Congress of the Suffolk County Massachusetts Resolves, looking towards organized resistance. On the adjournment of the Congress, he returned to Virginia where he continued to be active, as a member of the House of Burgesses, in urging on the organization, equipment, and training of troops, and even undertook in person to drill volunteers. His attitude towards the mother country at this time, however, must not be misunderstood. Much as he expected war, he was not yet ready to declare in favor of independence, and he did not ally himself with the party of independence until the course of events made the adoption of any other course impossible.

The Second Continental Congress

In March 1775, he was appointed a delegate from Virginia to the Second Continental Congress. He served on committees for fortifying New York, collecting ammunition, raising money, and formulating army rules. It seems to have been generally understood that in case of war, Virginia would expect him to act as her commander-in-chief, and it was noticed that he was the only member who habitually appeared in uniform.

History, however, was to settle the matter on broader lines. The two most powerful colonies were Virginia and Massachusetts. The war began in Massachusetts and troops from New England flocked to the neighborhood of Boston almost spontaneously. But the resistance, if it was to be effective, had to have the support of the southern colonies, and the Virginia colonel who was serving on all the military committees of Congress, and whose experience in the Braddock campaign had made his name favorably known in England, was the obvious as well as the political choice.

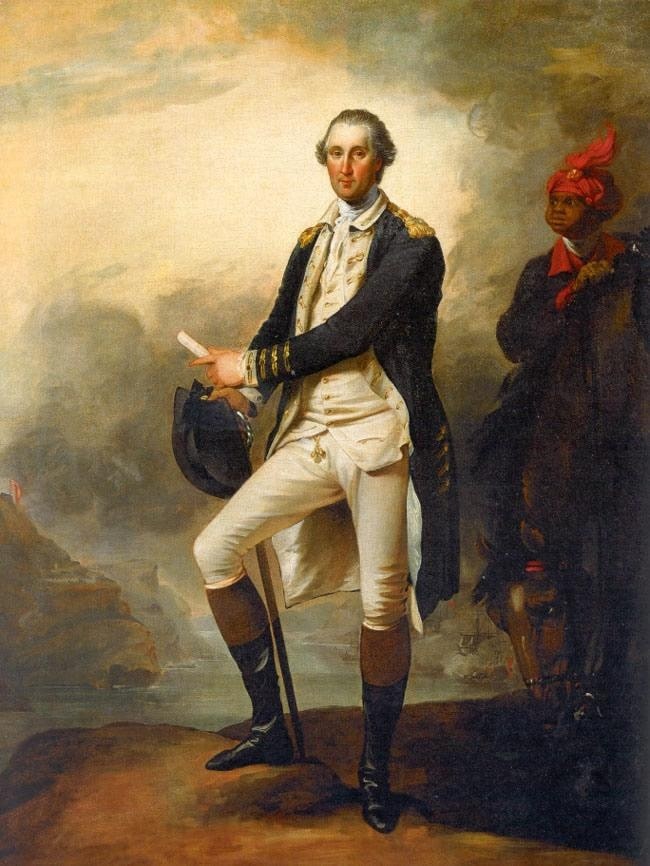

Commander-in-Chief and first battles

When Congress, after the fights at Lexington and Concord, resolved that the colonies ought to be put in a position of defense, the first practical step — on the motion of John Adams of Massachusetts — was the unanimous selection of Washington as Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces of the United Colonies (15 June). Refusing any salary and asking only the reimbursement of his expenses, he accepted the position, asking every gentleman in the room,

however, to remember his declaration that he did not believe himself to be equal to the command, and that he accepted it only as a duty made imperative by the unanimity of the call. He reiterated this belief in private letters, even to his wife; and there seems to be no doubt that, to the day of his death, he was the most determined skeptic as to his fitness for the positions to which he was successively called.

He was commissioned on 17 June 1775 and set out at once for Cambridge, Massachusetts. Contemporary accounts agree that Washington was an imposing presence. In his prime his height was six feet three inches — as given in his orders for clothes from London. His weight was about 220 pounds. The marquis de Lafayette said that his hands were the largest he ever saw on a man.

Evidently it was his extraordinary dignify and poise — forbidding even the suggestion of familiarity — quite as much as his stature, that impressed those who knew him.

On 3 July he took command of the Continental Army and the levies there assembled for action against the British garrison in Boston. The Battle of Bunker Hill had already taken place, news of it reaching him on his way north. Until the following March, Washington’s work was to bring about some semblance of military organization and discipline, to collect ammunition and military stores, to correspond with Congress and the colonial authorities, to guide military operations in widely separate parts of the country, to create a military system for a people entirely unaccustomed to such a thing (and impatient and suspicious under it), and to bend the course of events steadily towards driving the British out of Boston.

He planned the expeditions against Canada under Richard Montgomery and Benedict Arnold, and sent out privateers to harass British commerce. It is not easy to see how Washington survived the year 1775; the colonial poverty, the exasperating annoyances, the outspoken criticism of those who demanded active operations, the personal and party dissensions in Congress, the selfishness or stupidity which cropped up again and again among some of the most patriotic of his co-adjutors were enough to have broken down most men. The change in this one winter is very evident. If Washington was not a great man when he went to Cambridge, he was both a general and a statesman in the fullest sense when he drove the British out of Boston in March 1776. From that time until his death he was the foremost man of the continent.

The military operations of the war will not be detailed here, but they include Washington’s near defeat in the Battle of Long Island, and his escape through Manhattan to New Jersey. The manner in which he turned and struck his pursuers at Trenton and Princeton, and then established himself at Morristown, so as to make the way to Philadelphia impassable; the vigor with which he handled his army at Brandywine and Germantown; the persistence with which he held the strategic position of Valley Forge through the dreadful winter of 1777—78, in spite of the misery of his men, the clamors of the people, and the impotence and meddling of the fugitive Congress.

These are the times that try men’s souls,

wrote Thomas Paine at the beginning of 1776, and the words had added meaning in each year that followed. But Washington had no need to fear the test. The fiber of his public character was soon hardened to its permanent quality.

“The Conway Cabal”

The spirit which culminated in the treason of Benedict Arnold was a serious addition to his burdens — for what Arnold did, others were almost ready to do. Many of the American officers, too, had taken offense at the close personal friendship that had sprung up between the marquis de Lafayette and Washington, and at the diplomatic deference which the Commander-in-Chief felt compelled to show to other foreign officers. Some of the foreign volunteers were eventually dismissed politely by Congress on the ground that suitable employment could not be found for them.

The name of one of them, Thomas Conway, an Irish soldier of fortune from the French service, is attached to what is called the Conway Cabal,

a scheme for superseding Washington by General Horatio Gates, who in October 1777 succeeded in forcing British General John Burgoyne to capitulate at Saratoga, and who had been persistent in his depreciation of the Commander-in-Chief and intrigued with members of Congress. A number of officers and politicians were mixed up in the plot, while the methods employed were the lowest forms of anonymous slander. But at the first breath of exposure, everyone concerned hurried to cover up his part in it, leaving Conway to shoulder both the responsibility and the disgrace.

The Treaty of Alliance with France (1778) — following the surrender of Burgoyne — put an end to all such plans. It was absurd to expect foreign nations to deal with a second-rate man as Commander-in-Chief while Washington was in the field, and he seems to have had no further trouble of this kind.

Washington’s final battles

The prompt and vigorous pursuit of Sir Henry Clinton across New Jersey towards New York, and the Battle of Monmouth (June 1778), in which the plan of battle was thwarted by General Charles Lee, closed the military record of Washington — so far as active campaigning was concerned — until the end of the war. The British confined their operations to other parts of the continent, and Washington, alive as ever to the importance of keeping a connection with New England, appointed General Nathanael Greene to lead the Southern Campaign, and devoted himself to administrating the war and watching the British in and about New York City.

It was in every way fitting, however, that he who had been the mainspring of the war from the beginning, and who had borne far more than his share of its burdens and discouragements, should end it with the campaign at Yorktown and the surrender of General Lord Cornwallis (October 1781). Although peace was not concluded until September 1783, there was no more important fighting. Washington retained his commission until the 23rd of December 1783, when, in a memorable scene, he returned it to Congress in Annapolis, Maryland, and retired to Mount Vernon.

American Cincinnatus

By this time the popular canonization of Washington had begun. On hearing that Washington would resign his commission and retire from power, the King said if true that made Washington the greatest man in the world. He was compared to Cincinnatus, the Roman who was appointed dictator in 458 — and when the crisis was over, retired to his farm.

He occupied a position in American public life and in the American political system which no one could possibly hold again. He may be said to have become a political element quite apart from the Union, or the states, or the people of either. In a country in which newspapers had at best only a local circulation, and where communication was still slow and difficult, the knowledge that Washington favored something, superseded with many men, both argument and the necessity of information. His constant correspondence with the governors of the states gave him a quasi-paternal attitude towards government in general.

On relinquishing his command, he was able to do what no other man could have done with either propriety or safety: he addressed a circular letter to the governors, pointing out changes in the existing form of government which he believed to be necessary, and urging an indissoluble union of the states under one federal head,

a regard to public justice,

the adoption of a suitable military establishment for a time of peace, and the making of those mutual concessions which are requisite to the general prosperity.

His refusal to accept a salary, either as commander-in-chief or as president, might have been taken as affectation or impertinence in any one else; it seemed natural and proper enough in the case of Washington.

It is even possible that he might have had a crown, had he been willing to accept it. The army, at the end of the war, was justly dissatisfied with its treatment. The officers were called to meet at Newburgh, New York, and it was the avowed purpose of the leaders to march the army westward, appropriate vacant public lands as part compensation for arrears of pay, leave Congress to negotiate for peace without an army, and mock at their calamity and laugh when their fear cometh.

Less publicly avowed was the purpose to make their Commander-in-Chief king, if he could be persuaded to aid in establishing a monarchy. A letter written to him by Colonel Lewis Nicola, on behalf of this coterie, detailed the weakness of a republican form of government as they had experienced it, their desire for mixed government,

with him at its head, and their belief that the title of king

would be objectionable to but few and of material advantage to the country.

Washington put a stop to the whole proceeding

His reply was peremptory and indignant. In plain terms he stated his abhorrence of the proposal. He was at a loss to conceive what part of his conduct could have encouraged their address; they could not have found a person to whom their schemes were more disagreeable

; and, he charged them, if you have any regard for yourself or posterity, or respect for me, to banish these thoughts from your mind, and never communicate, as from yourself or anyone else, a sentiment of the like nature.

His influence, and his alone, secured the quiet disbanding of the discontented army.

Return to Mount Vernon

Washington’s influence was as powerful after he had retired to Mount Vernon as before the resignation of his command. The Society of the Cincinnati, an organization composed of officers of the late war, chose him as its first president; but he insisted that the Society should abandon its plan of hereditary membership, and change other features of the organization against which there had been a public clamor. When the legislature of Virginia gave him 150 shares of stock in companies formed for the improvement of the Potomac and James rivers, and he was unable to refuse them lest his action should be misinterpreted. He extricated himself by giving them to educational institutions.

His voluminous correspondence shows his continued concern for a standing army and the immediate possession of the western military posts, and his interest in the development of the western territory. From public men in all parts of the country he received such a store of suggestions as came to no other man, digested it, and was enabled by means of it to speak with what seemed infallible wisdom. Despite the burden of letter writing, tree-planting and rotation of crops (as evidenced in his diaries), and his increasing reading on the political side of history, he found time to entertain a stream of visitors from all parts of the United States and from abroad.

Among these, in March 1785, were the commissioners from Virginia and Maryland, who met at Alexandria to form a commercial code for Chesapeake Bay and the Potomac, and then visited Mount Vernon. From that moment the current of events, leading into the Annapolis Convention of 1786 and the Federal Convention of the following year, shows Washington’s close supervision at every point.

The Constitutional Convention

When the Constitutional Convention met in Philadelphia in May 1787, it rapidly disposed of improving the The Articles of Confederation and moved to frame a new constitution. Washington was present as a delegate from Virginia, though much against his will; and a unanimous vote at once made him the presiding officer. Naturally, therefore, he did not participate in debate; and he seems to have spoken but once, and then to favor an amendment reducing to 30,000 — from 40,000 —the minimum population required for representation in the House of Representatives. The mere suggestion, coming from him, was sufficient, and the change was at once agreed to. He approved the constitution, which was decided upon, believing, as he said, that it was the best constitution which could be obtained at that epoch, and that this or a dissolution awaits our choice, and is the only alternative.

As president of the convention, he signed the constitution, and kept the papers of the convention until the adoption of the new government, when they were deposited at the Department of State.

Washington used all of his vast influence to secure the ratification of the new instrument, and this was probably decisive. When enough states had ratified to assure the success of the new government, and the time came to elect a president, there was no hesitation. The office of president had been cut to fit the measure of George Washington,

and no one thought of any other person in connection with it. The unanimous vote of the electors made him the first President of the United States; their unanimous vote elected him for a second time in (1792—93); and even after he had positively refused to serve for a third term, two electors voted for him (1796—97).

President of the United States

While the success of the new government was the work of many men and many causes, one cannot resist the conviction that the factor of chief importance was the existence, at the head of the executive department, of such a character as Washington. It was he who gave to official intercourse formal dignity and distinction. It was he who secured for the president the power of removal from office without the intervention of the Senate. His support of Hamilton’s financial plans not only insured a speedy restoration of public credit, but also, and even more important, gave the new government a constitutional ground on which to stand. His firmness in dealing with the Whisky Rebellion

(1794) taught a much needed and wholesome lesson of respect for the Federal power.

His official visits to New England in 1789, to Rhode Island in 1790, and to the South in 1791, enabled him to test public opinion and at the same time increase popular interest in the national government. He was not a political partisan and he held the two natural parties apart, preventing party contest, until the government had become too firmly established to be shaken by them. It would be a great mistake, however, to suppose that the influence of the president was fairly appreciated during his term of office, or that he himself was uniformly respected. Washington seems never to have fully understood either the nature, the significance, or the inevitable necessity of party government in a republic. Instead, he attempted to balance party against party, selected representatives of opposing political views to serve in his first cabinet, and sought in that way to neutralize the effects of parties.

The consequence was that the two leading members of the cabinet, Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson — exponents for nearly opposite political doctrines — soon fought, to use the words of one of them, like two game-cocks in a pit.

Consciously or not, Washington had a natural bias for Federalist party; his letters to Lafayette and to Patrick Henry in December 1798 and January 1799, make that evident even without the record of his earlier career as president. It is inconceivable that, to a man with his type of mind and his extraordinary experience, the practical sagacity, farsightedness, and aggressive courage of the Federalists should not have seemed to embody the best political wisdom, however little he may have been disposed to ally himself with any party group or subscribe to any comprehensive creed.

Accordingly, about 1793 when the Democratic-Republican party came to be formed, it was not to be expected that its leaders would long submit with patience to the continual interposition of Washington’s name and influence between themselves and their opponents; but they maintained a calm exterior. Some of their followers were less discreet. The president’s proclamation of neutrality, in the war between England and France, excited them to anger and his support of John Jay’s treaty with Great Britain roused them to fury. His firmness in thwarting the activities of Edmond Charles Edouard Genet, minister from France, alienated the partisans of France; his suppression of the Whisky Rebellion

aroused in some the fear of a military despotism.

Forged letters, purporting to show his desire to abandon the revolutionary struggle, were published; he was accused of drawing more than his salary; his manners were ridiculed as aping monarchy

; hints of the propriety of a guillotine for his benefit began to appear; he was spoken of as the stepfather of his country.

The brutal attacks, exceeding in virulence even what happens today, embittered Washington, especially during his second term. In 1793 he is reported to have declared in a cabinet meeting that he would rather be in his grave than in his present situation,

and that he had never repented but once the having slipped the moment of resigning his office, and that was every moment since.

The most unpleasant portions of Jefferson’s Anas are those in which, with an air of psychological dissection, he details the storms of passion into which the president was driven by the newspaper attacks upon him. There is no reason to believe, however, that these attacks represented the feeling of any save a small minority of politicians. The people never wavered in their devotion to the president, and his election would have been unanimous in 1796, as in 1792 and 1789, had he been willing to serve.

Retirement and final years

Washington retired from the presidency in 4 March 1797 and returned to Mount Vernon — his journey marked by popular demonstrations of affection and esteem. At Mount Vernon, which had suffered from neglect during his absence, he resumed the plantation life which he loved, the society of his family, and the management of his slaves. He had resolved some time before never to obtain another slave, and wished from his soul

that Virginia could be persuaded to abolish slavery; it might prevent much future mischief

; but the unprecedented profitableness of the cotton industry, under the impetus of the recently invented cotton gin, had already begun to change public sentiment regarding slavery, and Washington was too old to attempt further innovation.

Visitors continued to flock to him, and his correspondence, as always, took a wide range. In 1798 he was made Commander-in-Chief of the provisional army raised in anticipation of war with France; he was fretted almost beyond endurance by the quarrels of Federalist politicians over the distribution of commissions. During these military preparations and following a long ride in a snow storm, he returned to Mount Vernon late. The next morning he came down with a seriously sore throat and had trouble breathing. This was aggravated by such contemporary remedies as blood-letting, gargles of molasses, vinegar and butter,

and vinegar and sage tea

— which almost suffocated him,

— and a blister of cantharides on the throat.

Within 48 hours, on 14 December 1799, Washington died. His last words were only business directions, affectionate remembrances to relatives, and repeated apologies to the physicians and attendants for the trouble he was giving them. Just before he died — according to his secretary Tobias Lear — he felt his own pulse, his countenance changed, the attending physician placed his hands over the eyes of the dying man, and he expired without a struggle or a sigh.

At age 67, he had lived several extraordinary lives. In his eulogy, Henry Lee eloquently summarized that Washington had been first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.

His remains rest in the family vault at Mount Vernon.