Contents

Contents

Quick facts

- Born: 8 March 1726 in London, England.

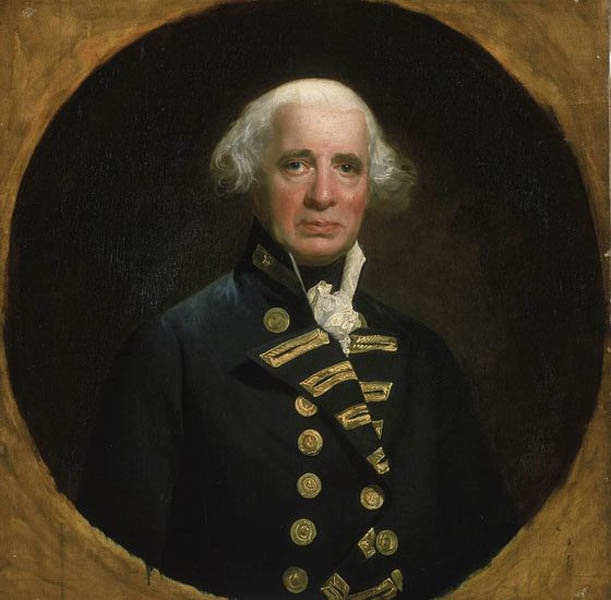

- Richard Howe, Earl Howe, was a British naval officer and admiral known for his command of the British fleet during the American Revolutionary War.

- He played a crucial role in the early stages of the war, particularly in the New York and New Jersey campaign, providing naval support that was vital for British operations.

- Despite his military role, Howe was sympathetic to the American cause and attempted to negotiate peace during the war, including the unsuccessful Staten Island Peace Conference in 1776.

- His leadership style was marked by a sense of fairness and concern for the welfare of his sailors, earning him respect from both his men and his adversaries.

- After the Revolutionary War, Howe continued his distinguished naval career, serving in various conflicts, including the French Revolutionary Wars.

- Died: 5 August 1799 in London, England.

- Buried at St Andrew’s Church, Langar, Nottinghamshire.

Biography

Richard Howe, British admiral, was born in London in 1726. He was the second son of Emmanuel Howe, 2nd Viscount Howe (who died while governor of Barbados in 1735), and of Mary Sophia Charlotte, a daughter of the Baroness von Kielmansegg, afterwards Countess of Leinster and Darlington.

Richard Howe entered the navy at age 13 and in 1740 transferred to the HMS Severn, one of the squadron sent into the South Atlantic in 1740. The Severn failed to round the Horn and returned home. Howe next served in the West Indies in the HMS Burford, and was aboard when she was very severely damaged in the unsuccessful attack on La Guayra in 1742. He was made acting-lieutenant in the West Indies in the same year; in 1744 his rank was confirmed.

During the Jacobite rising of 1745 he commanded the HMS Baltimore sloop in the North Sea. He was dangerously wounded in the head while cooperating with a frigate in an engagement with two strong French privateers. In 1746 he became post-captain, and commanded the HMS Triton in the West Indies. As captain of the Cornwall, the flagship of Sir Charles Knowles, he was in the battle with the Spaniards off Havana (2-Oct-1748).

During the peace between the end of the War of the Austrian Succession and the beginning of the Seven Year’s War (1748 – 54), Howe held commands at home and on the west coast of Africa.

In 1755 he went with Boscaweii to North America as captain of the Dunkirk. His seizure of the French Alcide was the first shot fired in the war. From this date till the peace of 1763 he served in the English Channel in various more or less futile expeditions near the coast of France, with a steady increase of reputation as a firm and skillful officer. On 20 November 1750, he led Hawke’s fleet as captain of the HMS Magnanime in the magnificent victory of Quiberon.

On 10 March 1758, Howe married Mary Hartop (1732 – 1800), the daughter of Colonel Chiverton Hartop of Welby in Leicestershire. They would have three daughters.

With the death of his oldest brother, George (killed near Ticonderoga on 6 July 1758), he inherited an Irish peerage and became Viscount Howe. In 1762 he was elected a Member of Parliament for Dartmouth, and held the seat until he received a peerage of Great Britain. During 1763 and 1765 he was a member of the Admiralty board, and from 1765 to 1770 was treasurer of the navy. In that year he was promoted rear admiral, and in 1775 vice admiral.

In 1776 he was appointed to the command of the North American station. The rebellion of the colonies was making rapid progress, and Howe was known to be in sympathy with the colonists. He had sought the acquaintance of Benjamin Franklin, who was a friend of his sister, a clever eccentric woman well known in London society, and had already tried to act as a peacemaker. It was doubtless because of his known sentiments that he was selected to command in America, and was joined in commission with his brother Sir William Howe — the general at the head of the land forces — to make a conciliatory arrangement. A committee appointed by the Continental Congress conferred with the Howes in September 1776 but nothing was accomplished.

The appointment of a new peace commission in 1778 offended the Admiral deeply, and he sent a resignation of his command. It was reluctantly accepted by Lord Sandwich, then First Lord, but before it could take effect France declared war, and a powerful French squadron was sent to America under the comte d’Estaing. Being greatly outnumbered, Howe had to stand on the defensive, but he baffled the French admiral at Sandy Hook, and defeated his attempt to take Newport at the Battle of Rhode Island by a fine combination of caution and calculated daring.

On the arrival of Admiral John Byron from England with reinforcements, Howe left the station in September. Until the fall of Lord North’s ministry in 1782 he refused to serve, assigning as his reason that he could not trust Lord Sandwich. He considered that he had not been properly supported in America, and was embittered both by the supersession of himself and his brother as peace commissioners, and by attacks made on him by the ministerial writers in the press.

On the change of ministry in March 1782 he was selected to command in the Channel, and in the autumn of that year (Sep – Nov), he carried out the final relief of Gibraltar. It was a difficult operation, for the French and Spaniards had 46 line-of-battle ships to his 33, and in the exhausted state of the country it was impossible to fit his ships properly or to supply them with good crews. He was, moreover, hampered by a great convoy carrying stores. But Howe was eminent in the handling of a great multitude of ships, the enemy was awkward and unenterprising, and the operation was brilliantly carried out.

From the 28 January to 16 April 1783 Howe was First Lord of the Admiralty; he held the post again in Pitt’s first ministry, from December 1783 until August 1788. The task was not a pleasant one, for he had to agree to economies where he considered that more outlay was needed, and he had to disappoint the hopes of the many officers who were left unemployed by the peace.

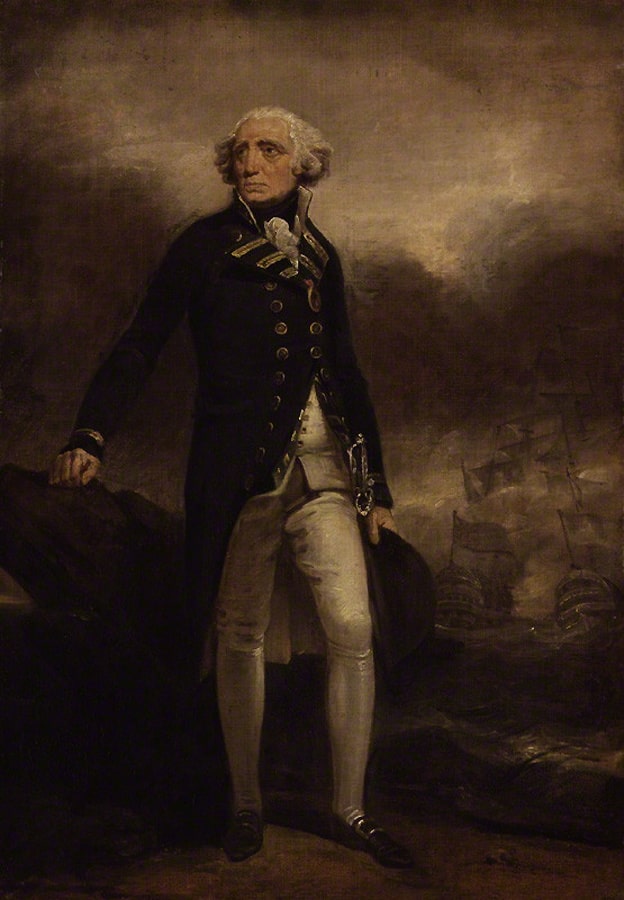

On the outbreak of the French Revolutionary war in 1793 he was again named to command the Channel fleet. His services in 1794 form the most glorious period of his life, for in it he won the epoch-making victory of the Glorious First of June. Though Howe was now nearly 70 — trained in the old school — he displayed originality not usual with veterans, and not excelled by any of his successors in the war, not even by Lord Nelson, since they had his example to follow and were served by more highly trained squadrons than his.

He continued to hold nominal command by the wish of King George, but his active service was now over. In 1797 he was called on to pacify the sailors mutinying at Spithead (near Portsmouth), and his great influence with the seamen who trusted him was conspicuous.

Having been created Viscount Howe of Langer in 1782 and Baron and Earl Howe in 1788, Howe was made a knight of the Garter in June 1797. He died in 1799 and was buried in his family vault at Langar. His monument by John Flaxman (1755 – 1826), completed 1811, is in St. Paul’s Cathedral. His Irish title descended to his brother General William Howe, who died childless in 1814.

Though no popularity hunter, Lord Howe was popular with the sailors, who knew him to be just. They called him Black Dick

because of his swarthy complexion and dark moods.