Contents

Contents

Quick facts

- Born: 20 March 1741 in Versailles, France.

- Houdon developed a consistent technique for creating his sculptures. He first modeled his sitter in terra cotta, a soft, unfired clay. From the unfired model, he made a more durable plaster cast. This cast was then used to produce marble busts and more plasters. Also, sometimes the plasters were given terra cotta patinations, or coatings, to achieve rich surface tones.

- As Minister to France (1784 – 89), Thomas Jefferson became acquainted with Houdon, discovered his talent, and soon considered him the best sculptor of the age.

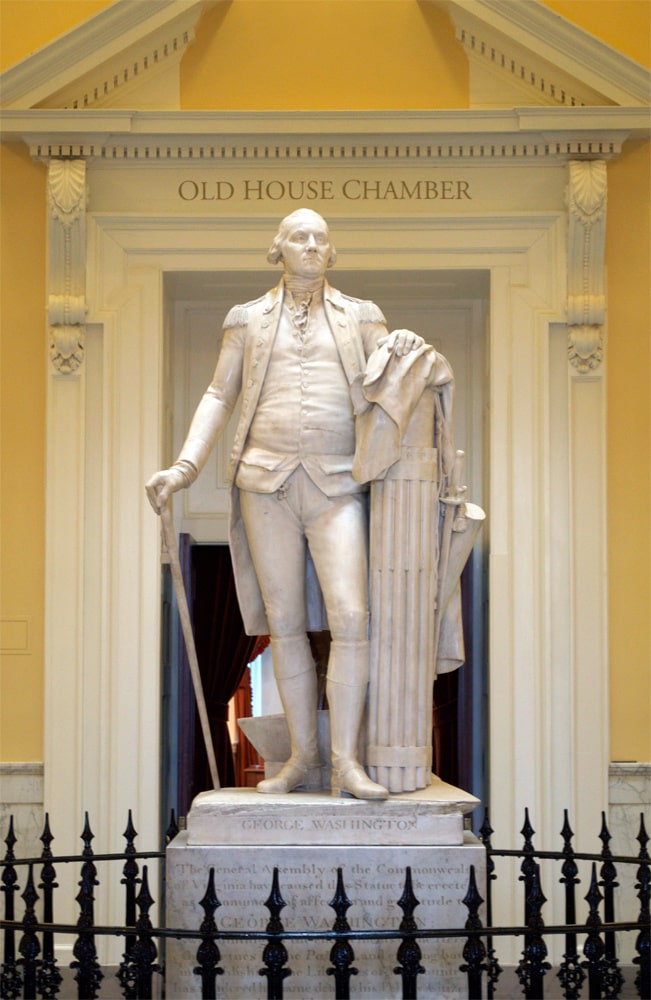

- When the Virginia General Assembly decided to honor George Washington with a statue (1784), Jefferson recommended Houdon, since no American sculptors seemed up to the task.

- With Washington, Houdon not only used his usual technique with a sitter, but he also made a plaster life mask.

- On seeing the finished statute of Washington, Marquis de Lafayette said, “That is the man himself.” Indeed, it was the most accurate image we have of Washington.

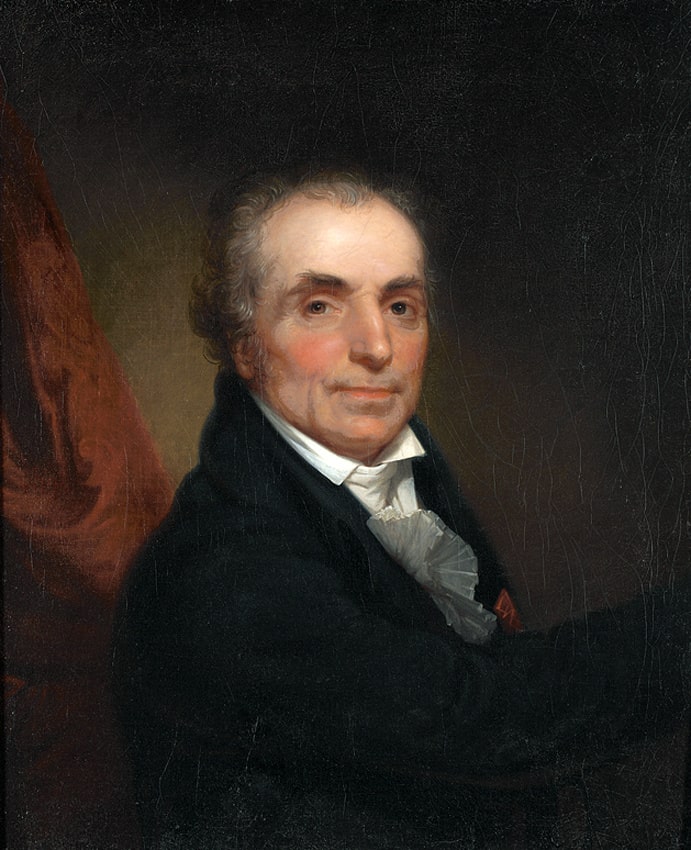

- Jefferson returned to America (Sep-1789) with some dozen terra cotta busts by Houdon, including American and French notables George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Marquis de Lafayette, John Paul Jones, and Voltaire.

- Jefferson also returned to Monticello with several copies of his own bust that Houdon had sculpted.

- Died: 15 July 1828 in Paris, France.

Biography

Jean-Antoine Houdon, French sculptor who also created definitive busts of American Revolution luminaries, was born at Versailles in 1740. At the age of 12 he entered the Ecole Royale de Sculpture, and at 20, having learned all that he could from Michel Ange Slodtz and Pigalle, he carried off the Prix de Rome and left France for Italy, where he spent the next ten years of his life.

His brilliant talent, which seems to have been influenced by the world of statues with which Louis XIV peopled the gardens of Versailles — rather than by the lessons of his masters — delighted Pope Clement XIV. After seeing the St. Bruno executed by Houdon for the church of St. Maria degli Angeli, the Pope reputedly said said he would speak, were it not that the rules of his order impose silence.

In Italy Houdon experienced the second Renaissance first-hand, and the direct and simple treatment of the Morpheus which he sent to the Salon of 1771 bore witness to its influence. This work procured for him his admission to the Academy of Painting and Sculpture, of which he was made a full member in 1775.

Between these dates Houdon was very active. He created busts of Catherine II and Diderot for the Salon of 1773; for the one in 1795 he produced not only his Morpheus in marble, but busts of the musician Gluck (in which the marks of small-pox in the face were reproduced with striking effect), Iphigeneia, and his well-known marble relief, Grive suspendue par les pattes. He took also an active part in the teaching at the academy and executed for the instruction of his pupils the celebrated l’Écorché (Flayed Man).

Each year Houdon was a chief contributor to the Salon and most of the leading men of the day were his sitters. Moliere, Voltaire, d’Alembert, Prince Henry of Prussia, Gerbier, Buffon, and Mirabeau are remarkable portraits; and in 1778, when the news of Rousseau’s death reached him, Houdon started at once for Ermenonville, where he took a plaster cast of the dead man’s face, from which he produced the grand and life-like head now in the Louvre.

In 1785, Thomas Jefferson arranged for Houdon to accompany Benjamin Franklin on his return to America in order to execute a a commission, from the state of Virginia, to create a sculpture of George Washington.

Houdon always worked from life, so he spent two weeks at Mount Vernon working on preliminary sketches and measuring and observing the General. As was his usual practice, Houdon created a terra cotta model, but with Washington he also created a plaster life mask. He had Washington lie down, coated his face with grease and covered his eyes before applying plaster; two quills in his nostrils allowed Washington to breathe. Afterwards, Houdon sculpted Washington’s eyes. When he returned to Paris he worked with these these as models, between 1786 and 1795, to sculpt a marble life-sized statue for the Virginia Capitol at Richmond. Houdon also used the life-mask to create other sculptures of Washington as well.

After his return to France, Houdon sculpted La Frileuse, (Winter) — a naif embodiment of shivering cold — as a companion to an earlier statue of Summer. It became, and still is, one of his most popular works.

With the French Revolution in 1789 interrupting his busy flow of commissions, Houdon took up a half-forgotten project for a statue of St. Scholastica. He was immediately denounced to the convention, and his life was only saved by his instant and ingenious adaptation of St. Scholastica into an embodiment of Philosophy.

He made a nude statue of Napoleon in 1806, but otherwise received little employment from the Emperor. He was, however, commissioned to execute the colossal reliefs intended for the decoration of the column of the Grand Army

at Boulogne, but ultimately it was used elsewhere. He also produced a statue of Cicero for the senate, and various busts, including Josephine and Napoleon, from whom Houdon was rewarded with the Legion of Honor.

He died in Paris in 1828.