Contents

Contents

Quick facts

- Born: 15 April 1741 in Chester, Maryland.

- During his long career, Charles Willson Peale painted about 1,100 portraits.

- Peale had never even seen a painting, much less tried his hand at painting, before 1762, when he was 21. Within 5 years, he was studying under Benjamin West in London and exhibiting with the Society of British Artists beside artists like Thomas Gainsborough.

- Between 1772 and 1795, George Washington sat for Peale a total of seven times — more than any other painter. These seven paintings from life were replicated, with variations, many times, by Peale and other painters in his family.

- Peale was a polymath. He developed expertise not just in painting, but also in such fields as carpentry, dentistry, optometry, shoemaking, taxidermy, and business.

- When John Isaac Hawkins patented the second physiognotrace (1802) — a mechanical drawing device — he partnered with Peale to market it to prospective buyers.

- Peale made improvements to another Hawkins’ device, the polygraph, a machine for making duplicates of letters. Thomas Jefferson used a series of these from 1806 until his death (1826). As Peale made improvements on the original design, Jefferson got a new one.

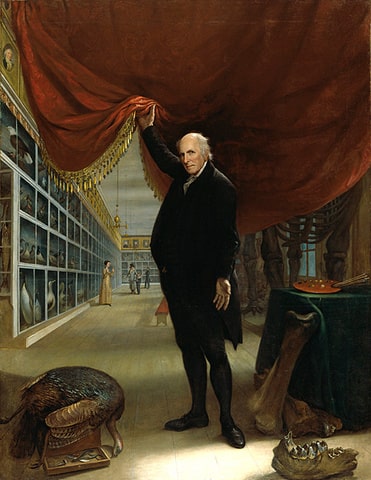

- Peale opened a portrait gallery of Revolutionary heroes (1782) and founded Peale’s Museum (opening to the public on 18-Jul-1786), an institution intended for the study of natural law, and the display of natural history and technological objects — which he ran from his home (on 3rd and Lombard Sts.) in Philadelphia.

- Running out of space for his collections, Peale rented space from the American Philosophical Society and moved the museum to Philosophical Hall (1794). Later, needing even more space, the museum was moved to the top floors of the old State House, now known as Independence Hall (1802).

- The most famous exhibit in Peale’s Museum was the mastodon, since its skeleton was the most complete then known — and zoologists all over Europe wanted to learn about it.

- Peale’s son, Rembrandt, opened a second museum in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1812.

- Today, the largest collection of Peale paintings can be seen at the Second Bank of the United States in Philadelphia.

- Died: 22 February 1827 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

- Buried at St. Peter’s Church, Philadelphia.

Biography

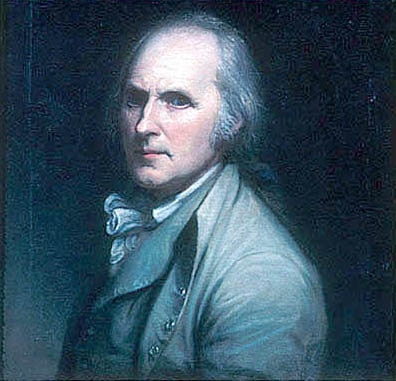

Charles Willson Peale, American painter — celebrated especially for his portraits of George Washington and his gallery of important figures from the American Revolution, was born in Queen Anne County, Maryland in 1741. During his infancy the family moved to Chestertown, Kent County, Maryland; after the death of his father (a country schoolmaster who had fled England because of embezzlement) in 1750 they settled in Annapolis. There, at the age of 13, he was apprenticed to a saddler.

About 1764 he began serious study of art. He received some assistance from Gustavus Hesselius, a Swedish portrait painter then living near Annapolis, and from John Singleton Copley in Boston. From 1767 – 70 he studied under Benjamin West in London.

Returning to America he opened a studio in Philadelphia in 1770 and met with immediate success. In 1772, at Mount Vernon, Peale painted a three-quarters-length study of Washington (the earliest known portrait of him), in the uniform of a colonel of the Virginia Regiment from the French and Indian War.

He painted various other portraits of Washington; probably the best known is a full-length, George Washington at Princeton (1779), of which Peale made many copies. This portrait had been ordered by the Continental Congress, which, however, made no appropriation for it, and eventually it was bought for a private collection in Philadelphia, and is now at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (which Peale co-founded in 1805).

Peale’s portraits of Washington may not be as iconic as those of Gilbert Stuart, but he was a skilled draftsman and colorist, and the range of his subjects gives to all of his work an unmatched historical value.

Peale moved to Philadelphia in 1777. He served as a member of the committee of public safety; aided in raising a militia company by painting battle flags, creating effigies of traitors

for political parades, and creating designs for publication; experimented with manufacturing (sorely needed) gunpowder; became a lieutenant and afterwards a captain in the Pennsylvania militia; and took part in the battles of Trenton, Princeton, and Germantown. In 1779 – 80 he was a member of the Pennsylvania assembly, where he voted for the abolition of slavery — he freed his own slaves whom he had brought from Maryland.

Peale can be considered the photographer of the Revolution,

because of his many bust-type paintings of the famous men of his time. While in the militia he painted miniatures of various officers in the Continental Army, and then later produced enlarged versions. His biographical portraiture, many of which can be seen at the Second Bank of the United States, was his founding project to create a pantheon that would perpetuate American republicanism and values.

In 1801 he undertook, largely at his own expense, the excavation of the skeletons of two mammoths in Orange and Ulster counties, New York. The reconstructed skeleton from the first excavation was later exhibited in his museum and memorialized in his painting The Exhumation of the Mastodon.

He died at his country home, near Germantown, Pennsylvania in 1827.