Contents

Contents

Quick facts

- Born: 10 October 1738 in Springfield, Pennsylvania.

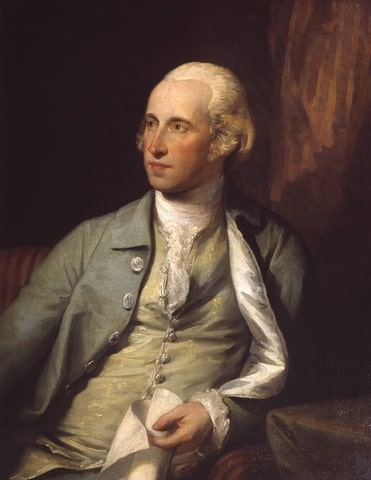

- Benjamin West was an American-born painter who gained fame and success in England as a history painter, particularly for his works depicting scenes from the American Revolution and British history.

- He became the second president of the Royal Academy in London, succeeding Sir Joshua Reynolds, and was a key figure in the development of the British school of painting.

- West’s most famous work, “The Death of General Wolfe,” depicting the death of British General James Wolfe at the Battle of Quebec, was groundbreaking for its use of contemporary dress rather than classical attire.

- Benjamin West’s enormous talent allowed him to succeed in London and become England’s leading neo-classical painter.

- He trained essential American painters of the American Revolution, including Ralph Earl, Charles Willson Peale, Rembrandt Peale, Gilbert Stuart, John Trumbull, and Thomas Sully.

- Died: 11 March 1820 in London, England.

- Buried at St Paul’s Cathedral, London.

Biography

Benjamin West, Anglo-American portrait and historical painter, was born in Springfield, Pennsylvania of an old Quaker family from Buckinghamshire, England in 1738. He was 25 when he visited London — and he never returned to America.

By age seven he began to show an affinity for art. According to a well-known story, young Benjamin was sitting by the cradle of his sister’s child, watching it sleep, when the infant happened to smile, and struck with its beauty, he got some paper and drew its portrait. This started him on his career, which with a perseverance that overcame many difficulties, allowed him at the age of 18 to establish himself in Philadelphia as a portrait painter. After two years he moved to New York where he met with considerable success.

In 1760 the assistance of friends enabled West to complete his artistic education by a visit to Italy. Remaining there for nearly three years, he acquired a reputation. He was elected a member to each of the principal academies of Italy.

He visited London in 1763, and stayed. He became known as an historical painter — and success soon followed. George III took him under his patronage and commissions flowed in. In 1768 he was one of the four artists who submitted to the King a plan for a Royal Academy.

West became one of its earliest members. In 1772 he was appointed historical painter to the King.

West devoted his attention mainly to the painting of large pictures on historical and religious subjects, conceived, as he believed, in the style of the old masters, and executed with great care and taste. So high did he stand in the public favor that on the death of Sir Joshua Reynolds (1792), he was elected his successor as president of the Royal Academy, an office he held for 28 years.

In 1802 he took advantage of the opportunity afforded by the Peace of Amiens to visit Paris and inspect the magnificent collection of the masterpieces of art at the Louvre, many of which had been pillaged by Napoleon’s armies from the galleries of nearly every capital in Europe.

On his return to London he devoted himself anew to his painting. Following a series quarrels with some of the members of the Royal Academy, he resigned his office in 1804. However an all but unanimous request that he should return to the chair induced him to recall his resignation.

At age 65 West had one of his greatest successes with one of his largest works, Christ Healing the Sick in the Temple. It had been intended to fulfill a request for a painting from the Board of Managers of Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia. However on its completion in 1811, it was exhibited in London to immense crowds, and was subsequently purchased by the British Institution for 3,000 guineas (a large sum for a contemporary painting). So West painted another and it was delivered to Philadelphia in 1817.

Most of his later works were similarly on the same grand scale, but none were as successful with the public. He died in London in 1820 and was honored with a burial in St Paul’s Cathedral.

During his lifetime West’s works were ranked with the great productions of the old masters. Generally, they are now considered a bit formal, tame, and lacking painterly freedom. But he did innovate. For example his Death of General Wolfe is interesting for introducing modern costume instead of the classical draperies which had been previously universal in similar subjects by English artists. In addition he was a teacher. Many American artists studied under West at his studio in London, including Ralph Earl, Charles Willson Peale, Rembrandt Peale, Matthew Pratt, Gilbert Stuart, John Trumbull, Thomas Sully, and Samuel F.B. Morse.