February 10 1763: French and Indian War ends

After nine years of war with the French, the British have cemented their control of the Thirteen Colonies, but are in a huge amount of debt. To repay the war loans, they look to begin implementing new taxes in the colonies.

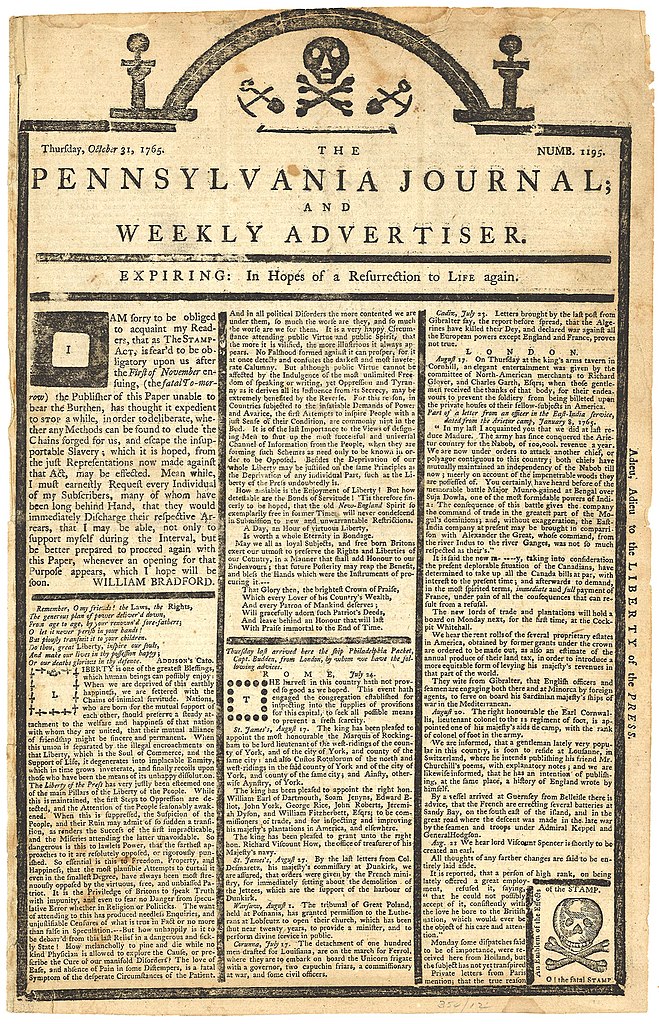

March 22 1765: Stamp Act is implemented

The Stamp Act was one of the single biggest causes of colonial discontent towards the British Crown in the New World.

It stipulated that most types of printed media, including everything from newspapers to playing cards, had to be printed on special British paper, which was sold with a large tax.

In response, there were widespread protests in the colonies against the Stamp Act. Protestors used the slogan “No taxation without representation”, highlighting the fact that despite paying huge amounts of taxes to Britain, the colonists had no representation in British parliament.

The Stamp Act was repealed on March 18 1766, but the British continued implementing other types of taxes to raise revenue in the colonies.

March 5, 1770: Boston Massacre

After continued efforts to implement unjust taxes on the colonists, such as through the Townshend Acts, discontent with the British was at an all-time high.

In the late 1760s, this was particularly true in Boston, which was a hotbed of protests, riots, and demonstrations against the British.

On March 5, 1770, two British soldiers guarding the Boston Custom House got into an argument with a local boy, which escalated to the point where they were surrounded by an angry mob of several hundred people.

The British were backed up by a handful of additional soldiers, but the situation kept escalating, until the point when one of them was knocked over by a projectile.

At this point, a volley of shots was fired into the crowd, hitting 11 people, and killing five.

Immediately, Patriot leaders labeled this incident the “Boston Massacre”. Paul Revere created an etching for propaganda purposes, showing the soldiers in a line, firing on a cowering crowd. In reality, the volley of shots was much less controlled, and no order to fire was given out as depicted in the image.

December 16, 1773: Boston Tea Party

In 1773, the British implemented the Tea Act in the Thirteen Colonies. This gave the East India Company, a British enterprise, an exclusive tax break on tea imports into America, allowing them to undercut the prices of colonial merchants and smugglers, who had previously profited from the tea trade.

In protest, on December 16 1773, the Sons of Liberty, a Patriot rebel group, boarded East India Company ships docked in Boston Harbor and threw approximately $1,000,000 worth of tea into the sea.

This alone was considered a huge crime by the British, but the Patriots did not stop there – in Philadelphia and New York, other East India ships were turned around, and this event led to even more unrest in the Thirteen Colonies.

September 5, 1774: First Continental Congress

On September 5, 1774, delegates from 12 of the 13 colonies met in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania to discuss British overreach and how to respond to the ever-worsening situation in America.

At this time, many people still held loyalties to the British Crown, and wanted a peaceful resolution to the crisis.

The delegates resolved, among other things, to implement a boycott of British imported goods, and to send a petition to King George III, which he rejected.

April 18-19, 1775: Paul Revere’s night ride

In April 1775, tensions continued to rise between the Loyalist and Patriot sides.

The British ordered General Gage and his troops to advance on Concord, MA, to capture colonial magazines, containing weapons, gunpowder, and artillery. The Patriots knew about this plan, and had moved their supplies, but the nearby town of Lexington was still of significant strategic significance.

On the night of April 18, 1775, Joseph Warren, a Sons of Liberty member in Boston, told Paul Revere and William Dawes that the British were planning to march on Lexington and Concord the very next day.

Revere and Dawes got on their horses and rode through the night towards Lexington, warning other Patriots along the way. He and other riders who had joined him were eventually captured near Concord, but their mission was a success: the Patriots had time to prepare for the British Army’s advance.

April 19, 1775: the shot heard ’round the world

The morning after Revere’s ride, the Revolutionary War officially started.

It is unclear to this day where the first shot was fired, and by whom. However, the conflict is widely considered to have started at Lexington Battle Green.

After the shot was fired, the Battles of Lexington and Concord kicked off, resulting in a significant victory for the Patriots.

June 17, 1775: Battle of Bunker Hill

The Battle of Bunker Hill was fought for control of the Charleston Peninsula – a strategically significant area in the fight for control of the city of Boston.

The British won the battle, but suffered a much larger number of casualties than the Patriots. Bunker Hill demonstrated that the rebels could hold their own against a larger, better-equipped, and better-organized militia.

June 19, 1775: Washington is appointed Commander-in-Chief

The Second Continental Congress made a significant amount of progress in organizing the Patriot military forces.

Up to now, the rebels had fought as a group of rag-tag militias, and Patriot political leaders wanted to make their forces more organized.

On June 14 1775, the Continental Army was officially formed, and five days later, on the 19th, the Congress appointed George Washington as Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces.

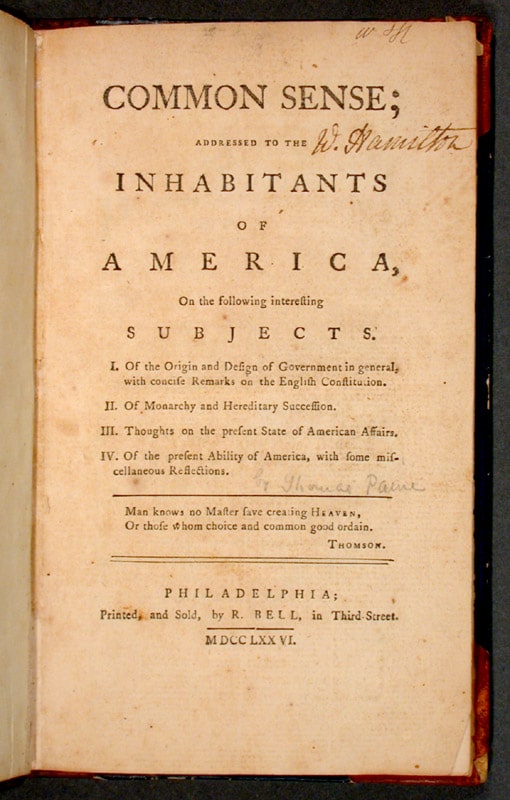

January 10, 1776: Thomas Paine publishes Common Sense

In the Thirteen Colonies, printed pamphlets were often used to spread news, propaganda, and other information to members of the public.

These pamphlets could be quickly printed, and were often read aloud in public places, meaning their messages could easily be distributed to tens or hundreds of thousands of people.

On January 10 1776, Thomas Paine published Common Sense, a political pamphlet that argued for independence from Great Britain. It spread like wildfire, and is estimated to have sold over 500,000 copies by the end of the Revolution.

Common Sense is considered one of the most effective pieces of propaganda used in the American Revolution, and likely helped to sway many people’s opinion in favor of war with the United Kingdom.

July 4, 1776: Declaration of Independence

On July 4, 1776, the Second Continental Congress formally declared the Thirteen Colonies independent from Britain, creating the United States of America.

The Declaration of Independence was signed by all 56 delegates to the Congress, and these men became known as the Founding Fathers of the United States.

Washington used the Declaration to inspire his troops, and its adoption led to the destruction of many symbols of the monarchy in areas of the country that the Patriots controlled.

December 25-26, 1776: Washington crosses the Delaware, beginning the Battle of Trenton

At the end of 1776, Continental Army morale was at a low point.

They had suffered a series of defeats, being completely driven out of New York, which also led to the loss of critical supplies as the army retreated. Many troops’ enlistments were about to expire, and Washington expected most of these soldiers would leave the Continental Army.

During the war, it was common for armies to set up camp and wait out the winter, due to the extremely harsh weather conditions. However, Washington had other plans.

He ordered his troops to cross the icy Delaware River, and launch a surprise attack on Hessian forces at Trenton, NJ. The Continental Army caught the Germans completely off-guard, and achieved a significant victory, boosting morale at a time it was desperately needed.

Washington’s crossing of the Delaware was arguably the most brilliant military move of the Revolutionary War.

October 17, 1777: Surrender of Burgoyne at the Battle of Saratoga

The ending of the Battle of Saratoga marked a turning point for the Continental Army.

British General John Burgoyne led an invasion force from Canada, hoping to join up with other units and take Albany, NY. These reinforcements never arrived, and he was eventually defeated, surrendering his entire army of more than 6,000 men to the Patriots on October 17, 1777.

This victory is credited with convincing France to officially join the war on the side of the Americans, further boosting Continental Army morale.

December 19, 1777 – June 19, 1778: Continental Army camps at Valley Forge

Despite the victory achieved at Saratoga, the Continental Army still faced significant hardships that would test the soldiers’ resolve.

In the winter of 1777-78, Washington decided to set up camp at Valley Forge, PA, partly because its elevated position offered protection against enemy attacks.

However, the British had raided the army’s supplies at the encampment a few months earlier. Combined with existing supply shortages, this left the Continental Army without adequate food or shelter for the winter.

Upon arriving at Valley Forge, men had to build their own huts, in freezing conditions, and Washington described a “famine” occurring in the camp.

It is estimated that over the winter, 2,000 people died of malnutrition and disease at Valley Forge.

Once the cold had subsided, some of the supply shortages were overcome, and Washington used the camp as an opportunity to train his men, with the help of Prussian army officer Baron von Steuben.

February 6, 1778: France officially joins the war

Following the victory at Saratoga, France officially entered the war as an ally of the United States.

It’s important to note, France had already been supplying the United States with weapons, food, and other materials for several years during the war. The beginning of the official alliance was significant though, as it offered a huge boost to Continental Army morale, and eventually led to French boots on the ground in America.

June 28, 1778: Battle of Monmouth

The Battle of Monmouth, fought in Freehold Borough, NJ, was one of the largest battles of the American Revolution, pitting Washington against the head of the British Army, General Sir Henry Clinton.

The result was inconclusive, but the Continental Army performed well, proving that Washington’s training camp at Valley Forge had been a success.

17 January, 1781: Battle of Cowpens

A significant victory for the Continental Army, this battle marked the beginning of the end of the American Revolution.

Led by Brigadier General Daniel Morgan, American forces used a clever tactical strategy against the British and American Loyalist troops under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton. Morgan’s tactics involved a staged retreat that lured the British into a position where they were surrounded, inflicting heavy casualties and capturing a significant portion of Tarleton’s force.

This defeat led General Charles Cornwallis to pursue the Americans into North Carolina, eventually leading to his army being trapped at Yorktown.

28 September – 19 October, 1781: Siege of Yorktown and British surrender

Having been defeated at Cowpens, the British were unable to achieve their goal of gaining control of the southern colonies. As a result, General Charles Cornwallis pursued General Nathanael Greene’s troops into North Carolina, leading to the Battle of Guilford Courthouse on March 15, 1781.

The British won the battle, but suffered significant casualties, and Cornwallis retreated to Yorktown with his troops.

In September, the Americans arrived in Yorktown, along with French naval and ground forces, and laid siege. On October 19, the British laid down their arms, and Cornwallis sent his second-in-command, Brigadier General Charles O’Hara, to formally surrender to the Americans and the French.

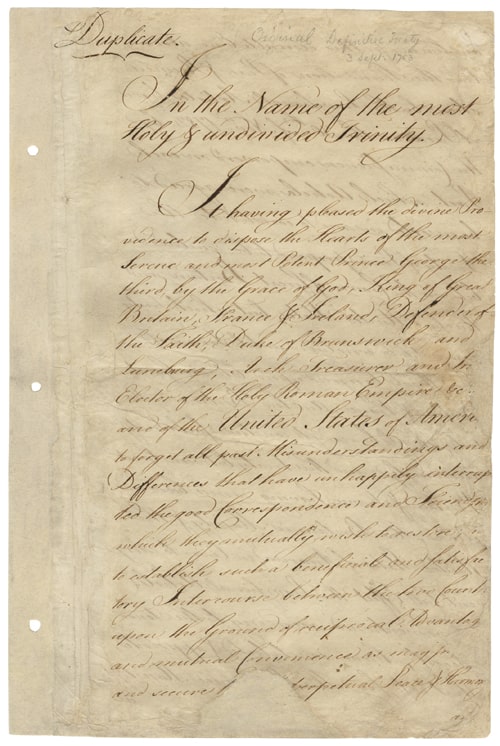

September 3, 1783: Treaty of Paris is signed

After more than a year of complex negotiations, a formal peace treaty was signed between the British and the United States, officially ending the American Revolution.

The treaty saw the United Kingdom relinquish huge amounts of land to the Americans, and officially defined the borders of the new nation.