Contents

Contents

Quick facts

- Born: 24 September 1755 near Germantown (in what is now Fauquier County), Virginia.

- As a boy, Marshall was influenced and encouraged by his father’s friend, George Washington.

- During the Revolutionary War, Marshall served first in the militia, then in the Continental Army, rising to the rank of Captain (1776 – 81).

- He participated in the Battles of Brandywine (1777), Germantown (1777), and Monmouth (1778). He also wintered at Valley Forge (1777 – 78), where General Washington appointed him chief legal officer.

- At the College of William and Mary, he studied law under George Wythe (1780).

- After President John Adams appointed him Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court (1801), he served through the administrations of Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, John Quincy Adams, and six years into that of Andrew Jackson.

- He served for over 34 years, the longest-serving Chief Justice of the Supreme Court to this day.

- Because Jefferson’s mother and Marshall’s maternal grandmother were first cousins, John Marshall and Thomas Jefferson were second cousins.

- Though distantly related, they detested one another; Marshall was a Federalist, Jefferson a Republican.

- Died: 6 July 1835 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

- Buried at Shockhoe Hill Cemetery in Richmond.

Introduction

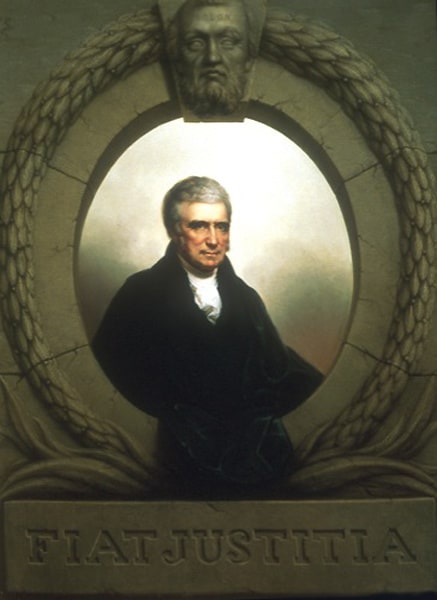

John Marshall, fourth Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, was born in 1755 at Germantown (now Midland), Virginia. He was the oldest of 15 children (six brothers and eight sisters) born to Thomas Marshall and Mary Isham Keith, the granddaughter of Thomas Randolph of Tuckahoe.

During the Revolutionary War Marshall served first as a lieutenant and after July 1778 as captain in the Continental Army. He resigned his commission early in 1781, was admitted to the bar after a brief course of study, and practiced in his native Fauquier County, and then, after two years, began practice in Richmond. In 1786 he became counsel in a case of great importance, Hite v. Fairfax, involving the original title of Lord Fairfax to that large tract of country between the head-waters of the Potomac and Rappahannock, known as the northern neck of Virginia. Marshall represented tenants of Lord Fairfax and won the high-profile case. From this time forward he was a formidable opponent in the Virginia bar.

In 1782 he married Mary Willis Ambler, the daughter of the then treasurer of Virginia. They had ten children, six of whom grew to full age.

Political career

He was elected to the Virginia Assembly (1782 – 91; 1795 – 97) and in 1788 he took a leading part in the Virginia Convention called to act on the proposed Constitution of the United States. Along with James Madison, he ably urged ratification. In 1795 President Washington offered him the attorney generalship, and in 1796, after the retirement of James Monroe, the position of minister to France. Marshall, however, declined both, because his situation at the bar appeared to him to be more independent and not less honorable than any other.

and his preference for it was decided.

He spent the autumn and winter of 1797 – 98 in France as one of the three commissioners appointed by President John Adams to work out differences between the young republic and the Directory. The commission failed, but the course pursued by Marshall was approved in America, and — along with the resentment felt because of the way in which the commission had been treated in France — on his return it made him exceedingly popular.

To this popularity, as well as to the earnest advocacy of Patrick Henry, he owed his election as a Federalist to the U.S. House of Representatives in the spring of 1799 — despite the overwhelming attachment in Richmond to the opposition, Republican, party. His most notable service in Congress was his speech on the case of Thomas Nash (alias Jonathan Robbins), in which he showed that there is nothing in the U.S. Constitution that prevents the Federal government from carrying out an extradition treaty.

He became Secretary of State in the last year of the presidency of John Adams (6-Jun-1800 to 4-Mar-1801), which overlapped with his appointment (31-Jan-1801) as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.

Chief Justice, 1801 – 1835

At the time of Marshall’s appointment it was generally considered that the Supreme Court was the one branch of the new government that had failed in its purpose. John Jay, the first Chief Justice — in an office with a life-time appointment — had resigned in 1795 to become Governor of New York. He left the bench convinced that the court would never acquire proper weight and dignity, since its organization was fatally defective.

The advent of the new Chief Justice was marked by a change in the conduct of the Court. Following the prevailing English custom, the judges had pronounced their opinions seriatim. But beginning with the December 1801 term, Marshall became practically the sole mouthpiece of the court. For 11 years the opinions were almost exclusively his, and there were few recorded dissents.

This change strengthened both the power and dignity of the Court. The Chief Justice embodied the majesty of the judicial department of the government almost as fully as the president stood for the power of the executive. That this change was acquiesced in by his associates without diminishing their goodwill towards him — and these were not men of mediocre ability — is testimony to the persuasive force of Marshall’s personality. Though this practice was abandoned shortly after Joseph Story became Associate Justice (Nov-1811), Marshall continued to deliver the opinion in the great majority of cases, and in practically all cases of any importance involving the interpretation of the Constitution. Expounding on the Constitution during the most critical period of its history was, therefore, his.

Four cases are of vital importance. In each of these it is Marshall who wrote the opinion of the Court. In each, the continued existence of the Federal system established by the Constitution depended on the action of the Court. In each, the Court adopted a principle which is now generally perceived to be essential to the preservation of the United States as a federal state.

- Marbury v. Madison. Decided two years after his elevation to the bench, Marshall ruled that it was the duty of the court to disregard any act of Congress, and, therefore — a fortiori — any act of a legislature of one of the states — which the Court thought contrary to the Constitution of the United States.

- Cohens v. Virginia. In spite of the contention of Jefferson, and the then prevalent school of political thought that it was contrary to the Constitution for a person to bring one of the states of the United States, though only as a respondent, into a court of justice, he held that Congress could lawfully pass an act which permitted a person who was convicted in a state court, to appeal to the Supreme Court, if he alleged that the state act under which he was convicted conflicted with the Federal Constitution or with an act of the U.S. Congress.

- M’Culloch v. Maryland. While agreeing that the Federal government is one of delegated powers and cannot exercise any power not expressly given to it in the Constitution, Marshall laid down the rule that Congress, in the exercise of a delegated power, has a wide latitude in the choice of means, and is not confined in its choice of means to those which must be used, if the power is to be exercised at all.By leaving Congress unhampered in the choice of means to execute its delegated powers, the ruling made it possible for the Federal government to accomplish the ends of its existence.

Let the end be legitimate,

said Marshall in the course of his opinion,let it be within the scope of the Constitution, and all means which are appropriate, which are plainly adapted to that end, which are not prohibited, but consist with the letter and spirit of the Constitution, are constitutional.

- Gibbons v. Ogden. Marshall held that when the power to regulate interstate and foreign commerce was conferred by the Constitution on the Federal government, the word

commerce

included not only the exchange of commodities, but the means by which interstate and foreign intercourse was carried on. Therefore Congress had the power to license vessels to carry goods and passengers between the states, and an act of one of the states making a regulation which interfered with such regulation of Congress was, o tanto, of no effect.By giving the Federal government control over the means by which interstate and foreign commerce is carried on, preserved the material prosperity of the country. The decision recognized what the framers of the Constitution recognized, namely that the United States is an economic union, and that business which is national should be under national, not state, control. Here Marshall established the Supreme Court as the final interpreter of the Constitution.

In all, Marshall decided 44 cases involving constitutional questions. Nearly every important part of the U.S. Constitution as it existed (including Amendments I – XII) is treated in one or more of them. The Constitution of today, in its most important aspects, is fundamentally the Constitution that he interpreted. If he did not completely work out the position of the states in the Federal system, he did grasp and establish the position of the U.S. Congress and the Federal Judiciary.

Assessment and impact

Chief Justice Marshall participated in over 1,000 decisions, 519 of which he wrote himself. Though he was a staunch advocate of Federalism (and a vigorous adversary of the Jeffersonian Republicans), he always adhered in his opinions to the Constitution as written.

To appreciate his accomplishment it is important to recognize that Marshall not only decided fundamental Constitutional questions, but that he also was able to convince those that studied them that the Constitution, as written, had been interpreted according to its evident meaning. The chief characteristic of his written opinions is the cumulative force of the argument. The ground for the premise is carefully prepared, the premise itself is clearly stated; nearly every possible objection is examined and answered; and then comes the conclusion. There is little or no repetition, but there is a wealth of illustration and a completeness of analysis that convinces the reader, not only that the subject has been adequately treated, but that it has been exhausted.

His style, reflecting his character, suits perfectly the subject matter. Simple in the best sense of the word, his intellectual processes were so clear that he never doubted the correctness of the conclusion to which they led him. Apparently from his own point of view, he merely indicated the question at issue, and the inexorable rules of logic did the rest. Thus his opinions are simple, clear, dignified. Intensely interesting, the interest is in the argument, not in its expression. He had, in a wonderful degree, the power of phrase. He expressed important principles of law in language which tersely yet clearly conveyed his exact meaning. As a result his opinions are practically devoid of theories of government, sovereignty, and the rights of man.

As a constitutional lawyer Marshall stands without rival. His work on international law and admiralty is of the first rank. He was not, however, a great common law or equity lawyer. In these fields he did not make new law or clarify what was obscure; in fact the constitutional opinions which today are found least satisfactory are those in which the question to be solved necessarily involves the discussion of some common-law conception, especially in those cases where he was required to construe the restriction imposed by the Constitution on any state impairing the obligation of contracts.

Of the wonderful persuasive force of Marshall’s personality there is abundant evidence. His influence over his associates is only one example — though an impressive one. From the moment he delivered the opinion in Marbury v. Madison the legal profession knew that he was a great judge. Each year, as his opinions piled up, his reputation increased as the full weight of his intellectual and moral qualities were revealed. To a very great degree Marshall impressed on the members of the bar, and on the profession generally, his own ideas on the correct interpretation of the Constitution and his own love for the union. He did this, not merely by his arguments, but by influence. Statesmen and politicians, great and small, were, almost without exception at this time, members of the bar. To influence the political thought of the bar was to a great extent to influence the political thought of the people.

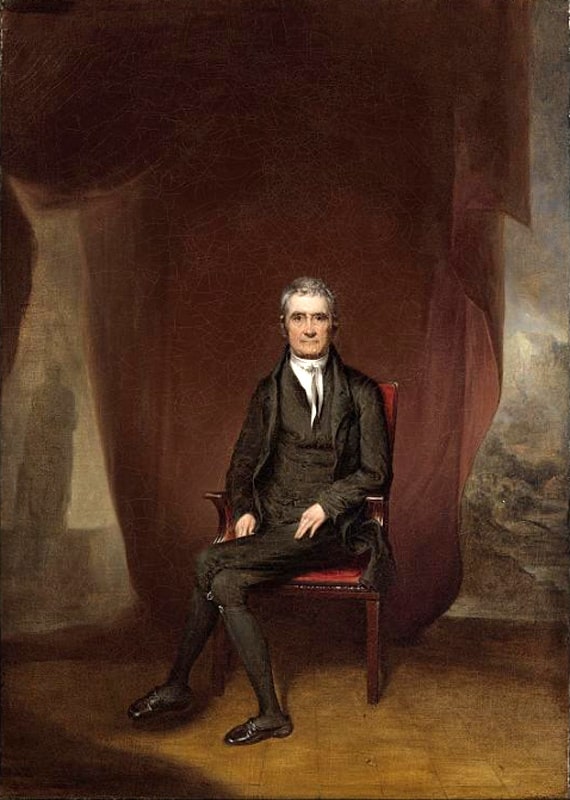

Private life and death

Marshal was a devoted husband. For the greater part of his 48 years of married life his wife Mary suffered intensely from a nervous affliction. Her condition called out the love and sympathy of her husband’s deep and affectionate nature. Judge Story tells us: That which, in a just sense, was his highest glory, was the purity, affectionateness, liberality and devotedness of his domestic life.

For the first thirty years of his Chief Justiceship his life was a singularly happy one. He never had to remain in Washington for more than three months. During the rest of the year, with the exception of a visit to Raleigh, which his duties as circuit judge required him to make, and a visit to his old home in Fauquier County, he lived in Richmond. His house on Shockhoe Hill is still standing.

On Christmas Day 1831 his wife died. He never was quite the same again. Returning from Washington in the spring of 1835 there was an accident to the stage coach in which he was riding and he suffered severe contusions. His health, which had not been good, now rapidly declined and in June he returned to Philadelphia for medical attendance. There he died in July.

His body, which was taken to Richmond, lies in Shockhoe Hill Cemetery under a plain marble slab next to his wife. He wrote his own simple inscription, giving facts of birth, marriage, death — but with no mention of his 34 years as Chief Justice on the Supreme Court.